Only the immature artist scoffs at the demands of form. “Free verse,” quipped Robert Frost, is like “playing tennis without a net.” There is a reason why the films of Terence Malick, as brilliantly associative as they are, tax our patience.

Only the immature artist scoffs at the demands of form. “Free verse,” quipped Robert Frost, is like “playing tennis without a net.” There is a reason why the films of Terence Malick, as brilliantly associative as they are, tax our patience.

Syd Field died on the 17th of this month. He was, along with Robert McKee, one of Hollywood’s most influential “gurus” on the art of screenwriting. Untold numbers of writers have learned from him, among them Tina Fey: “I did a million drafts. And then I did the thing everybody does–I read Syd Field and I used my index cards.”

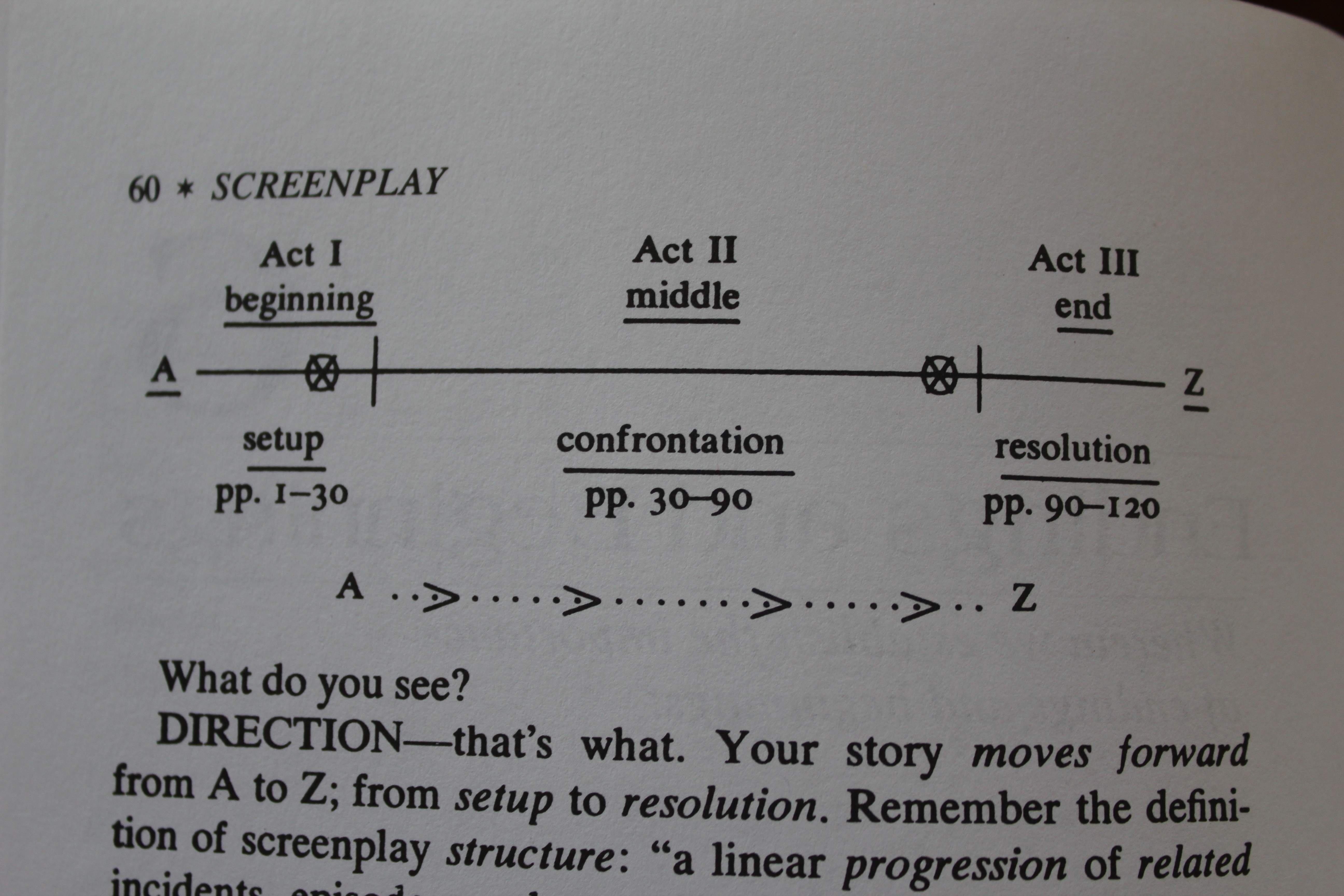

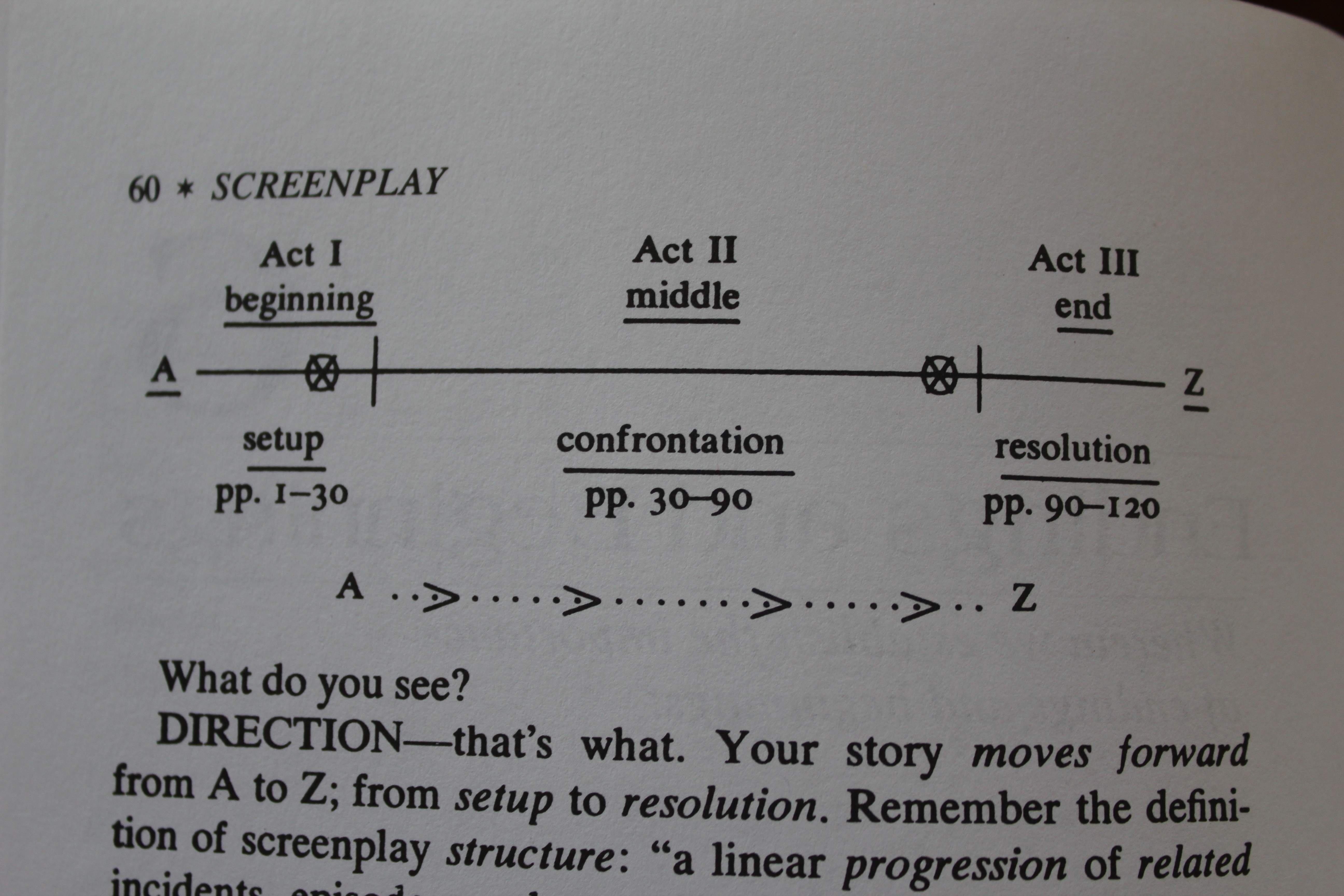

Syd Field wrote many books on screenwriting, but he is best known for Screenplay, first published in 1979 and revised several times since. In Screenplay Field clarifies the basic three-act structure of the modern film–and indeed, of all narrative art. Field did not invent this structure; we find Aristotle beginning to rough it out in his Poetics. But just as Watson and Crick did not invent DNA, but made known its structure, so Field, while not inventing story structure, made it eminently manifest to a contemporary audience.

Act I. An inciting incident upsets the hero’s plans and he is thrown into an adventure. Act II. The attempt to bring the adventure to a halt only results in further complication. Act III. The hero faces the ultimate obstacle to the resolution of his difficulty–an obstacle he either succeeds at overcoming, or fails.

Setup. Confrontation. Resolution.

That’s what a story is.

Field was particularly insistent upon writers knowing the ending of their story: “What is the ending of your story? How is it resolved? Does your main character live or die? Get married or divorced? Get away with the holdup, or get caught? Stay on his feet after 15 rounds with Apollo Creed, or not? What is the ending of your screenplay?” Field believed that the ending is the first thing a writer should know before writing his or her story.

Sound formulaic? Is Field only giving us a recipe for the conventional film with the “Hollywood ending”?

Consider, then, a more highbrow authority, Gilbert Murray (1886-1957), Regius Professor of Greek at Oxford, among other posts. “Most contemporary plays,” writes Murray in The Classical Tradition in Poetry, “admirable in detail and stagecraft as they often are, have weak last acts. Similarly, in the novel…you find a number of writers who can give exquisite studies of character, delicious conversations and individual scenes, but very few who can construct a story with a definite unity of effect and proper climax, or, to use the Greek term, “catastrophe.” One might almost say that they leave that high quality to the writers of detective stories.”

Listen to Professor Murray. The “definite unity of effect and proper climax” is today found most prominently in works of detective and other genre fiction, as well as, we might add, at the movies. Artistes may scoff at three-act structure as the slop of the “masses,” but Murray, notice, refers to it as “that high quality.” It is not a mistake, or in itself a sign of steep cultural decline, that scores of people will flock to their local multiplex this Thanksgiving weekend, rather than hunker down by the fire with Ulysses.

The central reason why three-act structure resonates so profoundly with the human spirit, such that we never tire of its rhythms, is that it allows us, in a most compressed and evident way, to contemplate our lives in miniature. Three-act structure is the structure of life. It is the imitation of ourselves being thrown into an adventure not of our choosing, and of working out a resolution to it in which we ultimately either succeed or fail. Field rightly lays emphasis upon the ending of a screenplay because the whole point of our lives is the ending. Will I realize who I was made to be, or not?

In his work Field gave storytellers not a recipe, but a set of principles applicable in an infinite variety of creative ways, ways as various as the adventures of individual human lives.

Thank you, Syd Field, for your life and work. May you rest in peace.

This article first appeared on Aleteia.